History of the breed

The Leicester sheep appears to have inhabited Leicestershire and its neighbouring counties for a long period before it was "improved".

"Cheap and Good Husbandry" (twelfth edition) written by Markham in 1668, mentions, on writing about the sheep of the Midlands at that time, "that the sheep of Worcestershire, many parts of Warwickshire, Leicestershire and part of Nottinghamshire, beareth a large boned sheep, of the best shape, and deepest staple; chiefly they be pasture sheep, yet their wool is coarser than that of Costal" (Cotswold).

It is therefore believed that there is no reason to assume that from many of the characteristics presented by the wool of the "new" Leicester breed that the parent stock was any other than the Longwool sheep of the Midland Counties.

It was this ordinary sheep of his district that Robert Bakewell used to develop his New Leicesters or Dishley Breed, apparently without having recourse to crossing, but by a confident reliance upon selection only. Bakewell's success was due to his firm faith in the power of animals to transmit their good qualities to their progeny, and a rigid determination to adhere to the type that he wished to produce. This was beauty of form, utility of form, early maturity and good fattening properties, he was apparently a little careless with regard to wool. Very little is known about how, he carried out his improvements since Bakewell was a very positive, secretive and self -reliant man and he left no records. He was a farmer who worked without ostentation, but his influence spread itself all over the world.

Robert Bakewell, of Dishley, began the improvement of his county breed of sheep in or about 1755. He possessed the ability to realise how properties of the parents may be transmitted to the offspring. The result of his work was the formation of an improved sheep, more symmetrical, thicker and deeper, with earlier maturity and better finishing qualities. At this time the wool was still neglected.

Bakewell's success is probably best indicated by the appreciation in which his sheep were held. It was stated that his first rams offered for "letting" only made 17s 6d each, the price rose to 100gns in 1786 for the letting of his stock. In 1789 he made 1,200gns by letting three rams and a further 2,000gns for seven other rams, he made a further 3,000gns by letting the remainder of his rams to the Dishley Society, a group of local farmers.

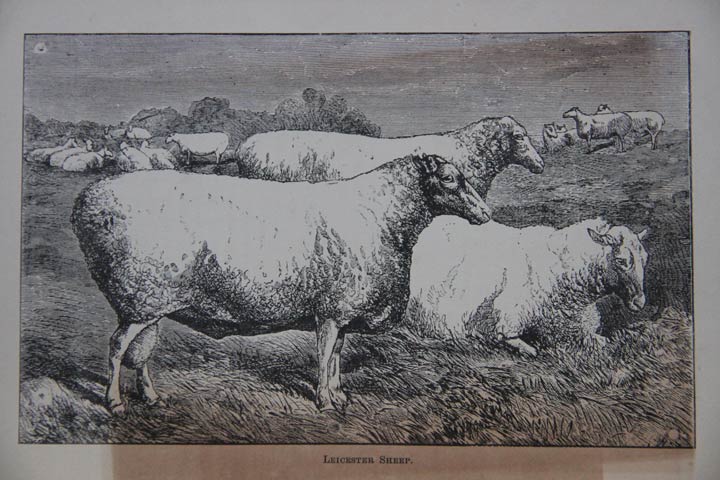

The Leicester sheep bequeathed to us by Bakewell could be described as white faced, hornless covered with a fleece having a length of 7-8 inches long, still of a somewhat coarse wool. The points were described as: Lips and nostrils black, nose slightly narrow and roman, but the general face being wedge shaped and covered in white hair; forehead covered in wool, although not always the case at that time, no horns, ears thin, long and mobile; a black speck on face or ear was not uncommon at that time; a good eye, short neck and level back; thick and tapering from skull to shoulders and bosom; breast deep, wide and prominent; shoulders upright and wide over the top; great thickness from blade to blade or "through the heart"; well filled up behind the shoulders, giving great girth; well sprung ribs, wide loins, level hips, straight and long quarters, tail well set on, good legs of mutton, round barrel, great depth of carcass, fine bone, a fine curly fleece free from black hairs, well covered back and loins, firm flesh, springy pelt, pink skin. The general form of the carcase square or rectangular, legs well set on, straight hocks, good pasterns, neat feet.

Bakewells's sheep were bred primarily for mutton to feed the movement of people brought from the countryside to the cities by the Industrial revolution. Current Leicesters still make very good mutton.

For the greater part of the 19th century the Leicester held its own as a commercial sheep, but in the 1920's and 1030's demand for a small lean carcase became the norm and it was gradually replaced by other breeds. It is still, although only one or two flocks in the North of England, farmed commercially due to its ability to do well on less favourable pasture and especially to survive the extremes of the winters, and at lambing time the lambs having a better covering of wool and the ability to get up quickly.

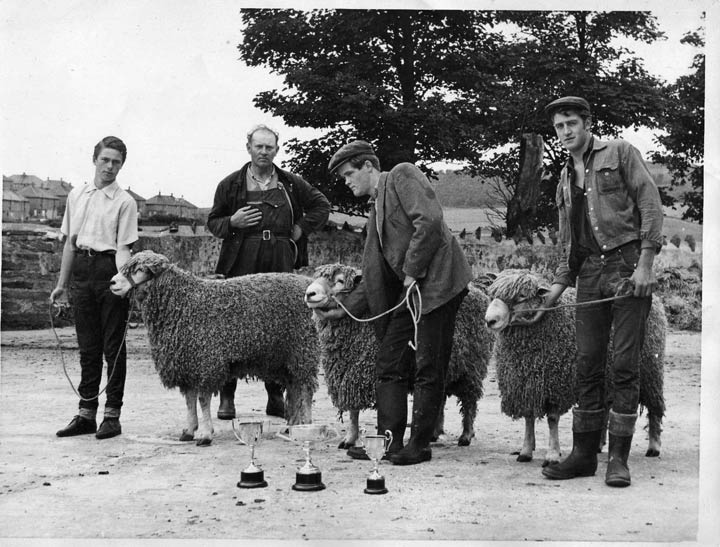

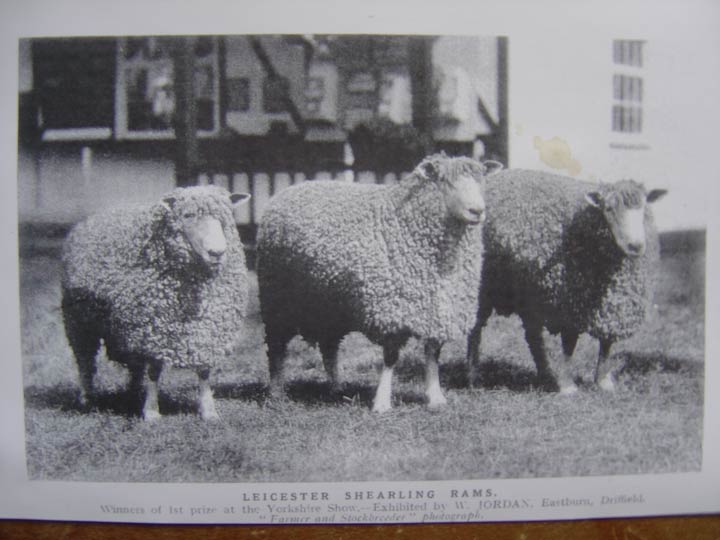

Since the formation of the Leicester Sheep Breeders' Association in 1893, in Driffield, North Yorkshire, later to become the Leicester Longwool Sheepbreeders' Association, great attention has been paid to its development, the result being a larger leaner sheep with better quality meat and weight of wool whilst retaining its old characteristics of early maturity. Sadly the national flock is in decline through no fault of the breed itself.

Do you know where there are any Leicester longwools we are always looking to increase the new bloodlines.